At Philips, The Semiconductor Line in Fishkill Runs on Python

| Category: | Software Development, Business |

|---|---|

| Keywords: | Rapid Application Development, Manufacturing, Quality, Fortune 500 |

| Title: | At Philips, The Semiconductor Line in Fishkill Runs on Python |

| Author: | Michael Muller |

| Date: | 2003/01/17 15:59:01 |

| Website: | http://www.philips.com/ |

| Summary: | At Philips, Python encodes business logic used to control its semiconductor manufacturing line in Fishkill, NY. |

| Logo: |

|

Introduction

This is the story of Python at the Philips semiconductor manufacturing facility in Fishkill, NY. This facility, originally built by IBM, was acquired by Philips in 2000. I have been involved with this facility on and off for the past twelve years and was responsible for redesigning substantial portions of the factory tool control software using Python.

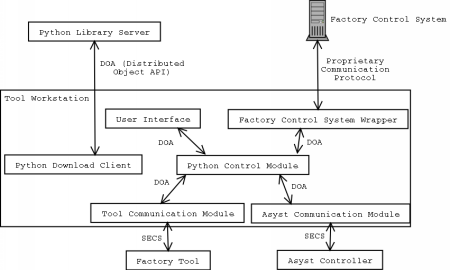

In the early 1990s, the factory adopted an automation strategy based around Asyst Technology's tool loader and unloader technology. This technology minimized contamination of semiconductor wafers by using robots to transport them between their sealed containers and the processing and measurement tools. As part of this change, control of the manufacturing line was decentralized and "tool workstations" were installed on most of the individual tools. These tool workstations replaced the existing area controller terminals as the primary interface to the factory control system, and also took on some additional tasks:

- Control of the tools and data collection from the tools using SECS, which is a communication protocol used in automation of electronics manufacturing facilities

- Dispatch of collected data to mainframe and PC databases. This data is used by manufacturing and engineering to monitor the product, and is also used to automatically tune the performance of the tools.

- Automation of logistical control by recording the arrival and departure of wafers at the tools. This had formerly been done manually.

- Presentation of a common user interface on all systems, where previously users had to work with the different interfaces presented directly by each tool.

- In many cases, control of the robot loader and unloader for the tool.

In the early 1990's architecture of the tool workstation software, it was broken up into a number of discrete components: The user interface, the SECS communication modules, the data collection interface, and so forth. The activities of each of these components were coordinated by a sequencing engine in each workstation. At that time, the components and the sequencing engine written were in C and high-level activities were sequenced in a simple proprietary scripting language.

This approach was used to develop Tool Application Programs (TAPs) for about 6 years. It was well understood by the developers, but had the following disadvantages:

- Since the majority of the coding was done in C, development of a TAP took 3-6 months. Likewise, debugging runtime errors in installed code required intense analysis.

- Most of the common code was not well modularized, making general changes in common business practice impossible.

- Tight coupling with system APIs married the code base to technologies on a path to extinction, such as OS/2 and several proprietary communication libraries.

Enter Python

After some time away from the facility, I returned to the Fishkill facility in 1997. At this time, I was charged with the task of redesigning the system architecture using modern technology, a project that was funded as a result of Y2K concerns.

In the course of building the infrastructure for this architecture, I developed my own object-oriented interpreted programming language, dubbed Bridge Scripting Language (BSL), as a substitute for the original sequencing language. I wanted to preserve and expand the ability to easily make changes to business logic without having to recompile code - a feature that is very useful when supporting a manufacturing environment. The original common business practice code of the system, as well as the specific business practice code for the first few TAPs, was written in BSL.

It was during this time that I became interested in Python. Python had many of the same features as BSL - clean, C-like syntax, easy to use dictionary and sequence types, and C/C++ extensibility. In addition, it had maturity, lots of documentation, and an active development community behind it.

Since supporting the BSL interpreter was becoming cumbersome, and because BSL code happened to be very easy to port to Python, I approached the senior developers with the suggestion that we change horses in mid-stream and replace BSL with Python.

This proposal was initially met with mixed reactions. There was some concern as to whether any scripting language (either BSL or Python) was really suitable for what amounted to the bulk of the code in the system. There was also a very strong contingent that favored porting significant portions of our BSL code to C++. As far as interpreted languages go, everybody seemed to have a preference that wasn't Python.

In the end, after much discussion, Python prevailed and the senior developers came to agree that moving to Python was the right thing to do. What ultimately closed the decision was the fact that it would have taken about three months to port the BSL code base to C++. It took two weeks to port it to Python.

This project eventually replaced almost every component of the original system. Areas of functionality that relied heavily on low-level APIs were rewritten in C++. The user interface was also rewritten in C++, in order to make use of the Visual Age User Interface Class Library. All of these components were addressable through a CORBA-like distributed object infrastructure.

The business logic that drives these components was written in Python, ninety percent of which is common to all of the tools.

Systems Architecture for Philips Semiconductor Manufacturing Line Zoom in

Results

This project was a huge success. We rebuilt eight years of software development effort from the ground up in less than two years, and with a substantially smaller team. I attribute this largely to Python. With Python, it is very easy to develop code quickly.

Based on my experiences in this project, I believe there are three reasons why Python facilitates rapid development:

- Python requires less supporting code. In most other languages, a significant amount code is needed just to get to the point of implementing an algorithm. In Python this is kept to a minimum: It is not necessary to declare variables or types, create iterators and other support objects, break code into particular files, or write other supporting code required in languages like C++ or Java. As a result, Python is almost executable pseudo-code.

- Python speeds the development cycle. Since Python code is compiled to byte code on the fly by the interpreter, the development cycle is just "edit-and-execute" instead of "edit-compile-execute". In practice, this can save substantial amounts of time.

- Python facilitates debugging. Python's detailed tracebacks reveal the cause of problems very quickly, usually immediately upon inspection. While there are debuggers available for Python, we were able to get along very well without them.

By using Python, largely because of the RAD features identified above, we realized the following additional benefits:

- Because the Python interpreter handles program errors by raising exceptions, and doesn't just crash as would a buggy C/C++ module, it was easy to capture and log unexpected errors seen on the assembly line. This allowed problems to be detected and resolved more quickly.

- Python made it easy to write support for gaining access to an already-running process, and to interactively probe the status of the code running there. This enabled efficient remote debugging and monitoring during development.

- The fact that Python is interpreted made it possible to modify and test code right out on the line. Previously, a return trip to the office was necessary for re-compilation of altered code.

Since this rewrite was completed, and because it was so successful, we've used Python in many other projects as well. For example, the library system that deploys software components to all of our workstations is now written in Python. The interface to the factory control system (a legacy system) was wrapped in Python to provide dynamic routing, a feature that allows certain manufacturing operations to be skipped depending on the circumstances. Python is also used to monitor servers, perform backups, for database maintenance, and for a variety of data analysis tasks.

Today, the tool workstation software team is involved in converting our systems from OS/2 to Linux. The portion of the system written in Python will require almost no changes for this port. It is also extremely likely that other system components currently written in C++ will be re-written in Python because of its portability and because time constraints almost prohibit any other possibility.

Conclusion

The Philips Fishkill TAP development team has accumulated a lot of experience with Python, and has developed an extensive body of code with it. They've found Python to be a robust and productive way to write, debug, and maintain complex systems. While they remain open to other technologies, Python continues to enable them to quickly provide solutions in the demanding domain of semiconductor manufacturing.

About the Author

Michael Muller is a software consultant who has been designing and programming network software systems for over 12 years. In addition to Python, he has extensive experience in C/C++, Perl, bash, Rexx, and Java. He has worked for UPS, MCI, Verizon (when they were Nynex), IBM, and Philips. Michael is one of the founding members of Enduden Consulting Inc. (www.enduden.com) through which he is available for contract work.